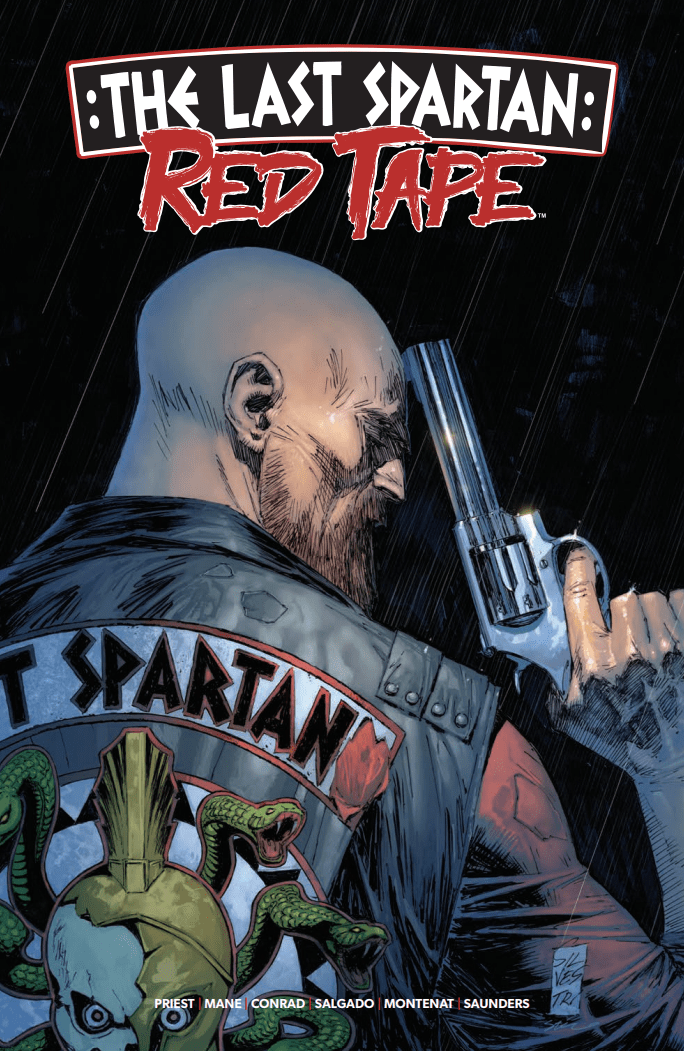

We sat down for an unfiltered interview with Christopher Priest, the writer who famously rewrote the book on Black Panther. His latest graphic novel, The Last Spartan: Red Tape, co-written with actor/producer Tyler Mane and writer/editor Renae Geerlings, tackles the brutal issue of human trafficking. This is part two of our conversation with the creative trio, and you can read our previous conversations with Tyler Mane and Renae Geerlings.

In this chat, Priest details the challenge of giving victims a voice in The Last Spartan and crafting a “very twisty” story. He also addresses his return to Black Panther in “The World to Come,” calling it a story about what gets passed down—and how he views T’Challa as a brilliant operator, “like Michael Corleone.” Don’t miss this rare, wide-ranging discussion about the ethics behind his characters, the behind-the-scenes fight to keep his most controversial lines, and why he believes in writing stories that hit hard and make a real impact.

The Making of The Last Spartan

Phillip Creary (PC): The story of The Last Spartan is inspired by the John F. Sanders novel of the same name. How did you, Tyler, and Renae approach adapting and expanding this novel for the graphic novel format? What were some elements you absolutely knew you wanted to keep, and what were some you wanted to rework?

Christopher Priest (CP): Well, first of all, this was entirely their [Tyler Mane and Renae Geerlings] idea. Tyler was initially looking to adapt the book for a streaming show or a film. In the current business climate, it’s often cheaper to produce a graphic novel than to shoot a pilot episode. Sometimes, people in the business world lack creative vision, and sometimes it’s difficult to describe a concept. It’s much easier to show them what it looks like. A comic book serves as a visual presentation, almost like a collection of storyboards.

Tyler and Renae were truly passionate about the book. They talked to my agent, and it just so happened that we were all living in the same town at the time, which made meeting in person much easier.

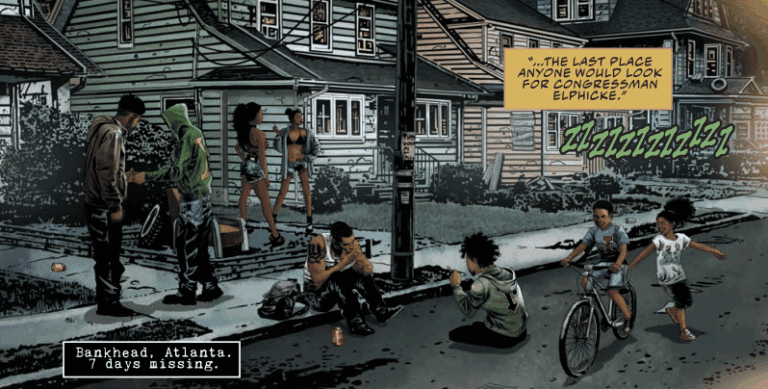

We wanted to keep the basic premise and core story beats of the novel: a former biker is forced back into the life he left to honor a personal debt after a grandchild is snatched and pulled into the human trafficking pipeline. The rule of the game seems to be that if a child is missing for more than 48 hours, they are considered gone, lost down the rabbit hole. This is a story about a guy who goes down that rabbit hole and succeeds.

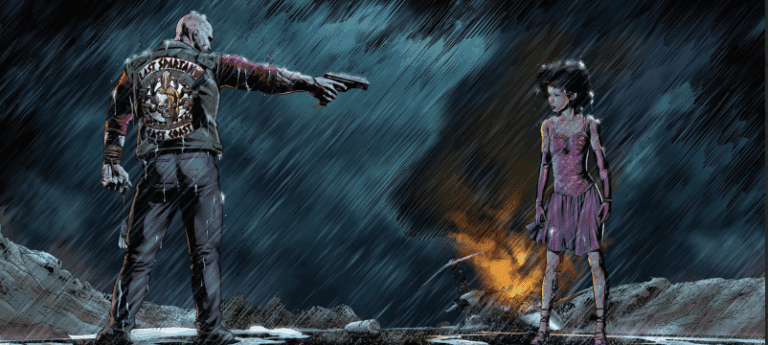

However, I had a great concern that a lot of what was in the novel, which was written quite a while ago, would today be considered cliché. For instance, we couldn’t just use the missing girl as a prop; we had to give the kid some agency. So we introduced an escalation toward the third act. We “flipped the script” on the teenage victim, who begins demonstrating initiative and a depth we didn’t initially see, and we actively played against the expectation of the “helpless kidnapping” victim.

My approach as a writer is to anticipate where the audience thinks the story is going and then use that expectation against them. You read a million comics, and you’re sure A leads to B leads to C. Not this book. You really have to pay attention because it gets very twisty.

Mane Entertainment

Tackling Human Trafficking and Social Awareness

PC: The Last Spartan handles the intense and intimate subject of human trafficking. What drew you specifically to this difficult topic, and why did you feel this was a story that needed to be told?

CP: Honestly, it was how Renae and Tyler sold it to me. They were incredibly passionate about the subject and the book. I’m pretty sure, as with most things, I had to be talked into it, because I’m incredibly lazy. I knew it would be a real challenge.

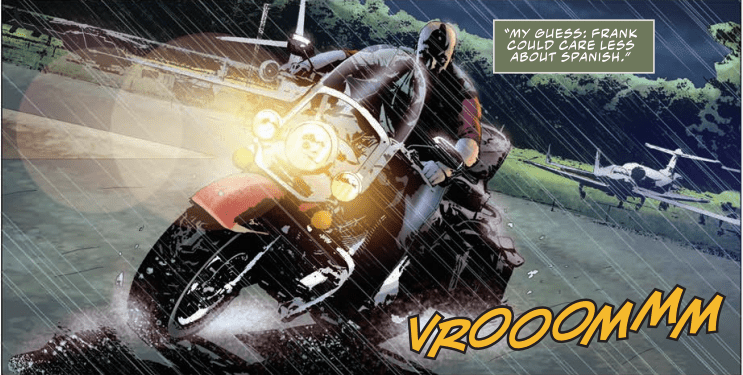

So, I wasn’t necessarily drawn to the subject matter itself; I was sold by their infectious enthusiasm. I felt I could bring something valuable to the work, and it’s obviously a good cause. It also forced me to research and learn about things outside my usual domain, like motorcycle gangs, which have a strict set of rules.

PC: The Last Spartan explicitly works with the Delivery Fund organization. How do you view the role of fiction or comic writing in driving real-world social awareness and action?

CP: I think it’s a backdoor into people’s consciousness and conscience. It’s easy to gloss over a 15-second “feed the children” ad. But if you’re immersed in a compelling, 90-minute drama, art and music have a way of flying below the radar and invading people’s minds, raising awareness.

We have to do it in a way that is entertaining, not preachy, and that has a sense of verisimilitude (the appearance of being real or true). My work tends to be very grounded in reality. We tried not to pull any punches, which is why there’s intense language and situations. We avoided the “sugarcoating” or “spoon-feeding” often seen in modern comics. I write more like Netflix’s Daredevil—raw, where characters get winded and fights feel real, not like the heightened reality of the CW’s Legends of Tomorrow.

My ultimate goal as a writer is to make you feel something. Whether it’s in The Last Spartan or a book with an absurd premise like Vampirella, there must be human moments that pull at your heartstrings and make you go, “Holy crap.”

Mane Entertainment

Amanda Harper: The True Believer

PC: Let’s talk about Amanda Harper. When she mentions that her unit was pulled right before the girls vanished, what drives her reaction—a personal sense of guilt or professional fury over corruption?

CP: What’s interesting about Amanda Harper is that she is essentially being trafficked by the government. She is sent undercover to investigate, and female undercover officers are constantly at risk for sexual or physical assault. Harper accepts this as part of the job. On TV, they clean this up, but the reality is that the possibility is always there.

She is a “true believer.” The main character, Frank Kane, is only motivated by his personal debt—he wants to find this one girl. Harper wants to save all the girls. This makes her a pain because she often improvises or goes off-script when Frank needs her, because she sees the other victims and wants to get them all out.

She is also a character dealing with trauma and self-medicating with alcohol. She’s “kind of screwed up” and not a healthy person. In a way, she is manipulating and lying to Frank, just as she is being used by the federal agencies, if it serves her purpose of unlocking the door for all the girls, not just the “little white girl.”

Mane Entertainment

Frank Kane: The Code-Driven Protagonist

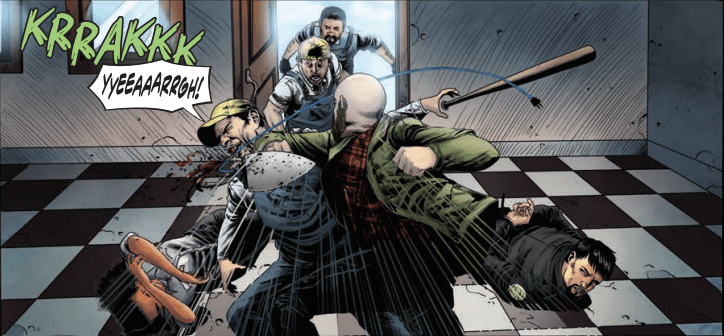

PC: Frank has a clear code; violence is a kind of drug to him, but he makes a promise not to shoot anyone and uses blanks. Can you talk about that tension?

CP: Frank is similar to Slade Wilson (Deathstroke) but driven by a different algorithm. Frank is firmly invested in the Spartan culture and its code of ethics. We had discussions about whether Frank should kill. He’s not a villain like Slade, but he is a guy who will beat you to death with a ream of copier paper. He won’t shoot you, but he’ll find inventive ways of dispatching you as needed.

He follows his own code of ethics, much like Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian. You can hamstring Frank with his own ethics. That restraint is what makes the character interesting. As a writing tool, it forces you to be more creative in solving the plot problem without breaking the rules you’ve set for the reader. Even when disappointed or ambushed, Frank will uphold his end of the code because that code is all he has.

Mane Entertainment

Privilege and Painful Realities

PC: The line, “I’m young, pretty, white. It’s the genetic lottery,” hits hard. Could you walk us through your intentions behind including that line?

CP: The line was meant to give the character of Jenny, the girl who is kidnapped, agency and awareness. For the first half of the book, she’s merely a prop. We needed to make her a legitimate person who participates in her own rescue.

The line is first said by Zhao, a shady character, who notes, “A young white virgin is top dollar.” Jenny later echoes this, showing she is aware that her physical appearance is a genetic gift, nothing she earned, and an “e-ticket” or a fast pass in life. It’s a statement of reality, not necessarily an attempt to open a dialogue about privilege, but to underscore the extreme value placed on this specific kidnapped child, which is why it would be so much harder for Frank to find her.

PC: Harper’s line: “Guns were made to put n****s on their backs.” What was the intent behind that powerful, controversial line?

CP: I had to fight to keep that line in there. Harper is being literal with that statement. Historically, the issue of guns in this country was about controlling slaves and keeping weapons out of the hands of Black people. The point she was making was to clarify that the disruptive technology of weaponry, particularly gun ownership in America, was designed to repress Black people.

The line works because it smacks the reader right in the head, and it locks in Amanda Harper’s character as a thoughtful person who has considered these deeper issues. It shows that she is on a mission that is bigger than her job: she wants to save all the girls—the brown, the Black, the Asian—not just the one white girl the agency is focused on.

Marvel

Black Panther: The World to Come and Legacy

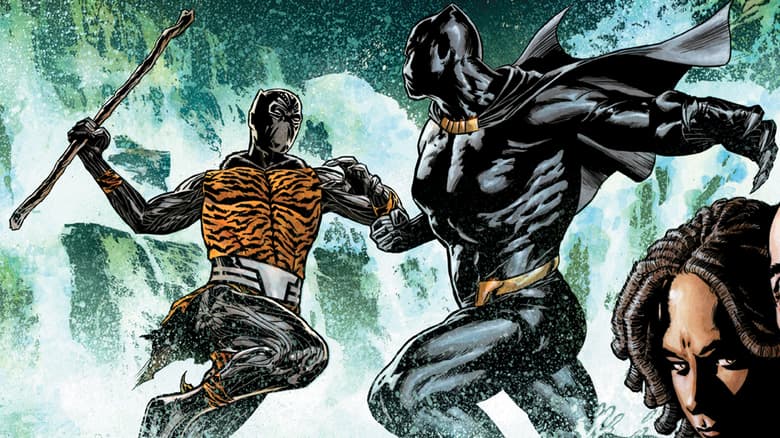

PC: Revealing Katama, a white character, as the new heir to the Black Panther caused a massive stir. Was hitting the readers with that kind of shock the main point, or was it a crucial step to dip into the bigger themes of legacy?

CP: No, it wasn’t the main point. The reaction completely caught me by surprise. When the issue was drawn, my concern was that longtime fans would immediately recognize the character as a connection to Everett K. Ross (Black Panther’s handler) and that the twist would be given away. I was so focused on who the character was that I completely dismissed the part about him being white.

The subsequent media hoopla was frustrating because people were missing the entire point of the story, which is about legacy. This book isn’t about Trump, or politics, or Democrats or Republicans. It just so happens that the real world has progressed in a bizarrely parallel way to the story we wrote years ago.

The World to Come is really about legacy and succession. It reflects on my and Joe Quesada’s (the co-writer) careers—what happens to the Panther toys when T’Challa finally hangs it up? It addresses the question of how creators of our “vintage” age out of a business that’s always looking for “shiny and new.”

The idea that we would “race swap” Black Panther is ludicrous. Never assume that I’m an idiot, or that Panther is an idiot. Panther is the smartest guy in the Marvel universe, and a lot of writers fail to honor the template set by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby in Fantastic Four #52: T’Challa is a duplicitous, incredibly smart, and technologically proficient guy whose main job is to protect Wakanda at all costs.

He’s not a hero like Bruce Wayne; he is Michael Corleone. He thinks five or six steps ahead and will frequently manipulate people, which is what the whole series is about. Whatever you think Black Panther is doing, you’re probably wrong. The clues are in front of you; you just have to slow down and read it.

CP (Final Words to Fans): Hang in there. We are obviously going somewhere. It’s a book about succession and a family feud about how to pass on this legacy. At the same time, we’re explaining the enormous potential T’Challa had to impact the world, and why he chose not to. Katama is unleashing his will upon the world, and it asks: if Katama could do it, why didn’t T’Challa? I think T’Challa realizes that wielding that much power could make Wakanda a totalitarian force. The book is ultimately about moving on, facing the end of a path, and hopefully showing that the old guys, we still know how to get it done.

From Toilet Humor to Prison Barter

PC: Let’s get back on track! Frank having that serious conversation on the toilet was a laugh-out-loud moment. I’m a firm believer in no talking on the toilet. Does Christopher Priest believe we should have more conversations on the toilet?

CP: [Laughs] No, no. That was simply Christopher Priest writing a guy who spent a long time in jail. In prison, there is no privacy, and that’s just common. But more to the point, I thought it would be amusing.

I was thinking, “How can I write this scene where Amanda [Harper] shows up at a crime scene and discovers Frank there?” Instead of the reader’s expectation—Frank standing there like Batman—we confound that expectation. The last thing you expect to see is a guy sitting on the throne. I ran it by Tyler and Renae, and they loved it. It was a moment that developed Frank’s character.

PC: This is a deep cut: Frank gets a photo of Jenny and a pie while in prison, which he never eats because he barter it to some natives. What kind of pie is it, and why does he trade away a perfectly good pie?

CP: I think, in prison, it’s currency. Fresh baked goods, like a mom’s apple pie, are worth way more than a carton of cigarettes in jail. You can negotiate and barter for things with it. And given that Frank is the kind of guy who wants to stay in shape, he’s not going to eat that pie anyway.

Deathstroke: Villain, Father, and Philosopher?

PC: Switching to Deathstroke: What are your thoughts on the Nightwing vs. Deathstroke rivalry? Is Dick Grayson his true nemesis, or is it Batman, or is it the whole DC Universe?

CP: There are two answers to that. One of my major problems writing Deathstroke was the slavish adherence to continuity; I was routinely turned down when I wanted to use DC heroes as enemies.

For one, I don’t think Slade gives a crap about Batman. I think that whole “Deathstroke vs. Batman” conflict (over the possibility of him being Damian Wayne’s father) was all on Batman. Slade told him in the first chapter: “Don’t start this, because you don’t know where it’s going to end… Robin lives, Robin breathes because I allow it.” Slade told him right away that the DNA results were fake, but Batman was insecure and obsessive.

Now Nightwing is a different story. Slade blames the Teen Titans, especially Nightwing, for the death of his son, Grant. That enmity is more misdirected; he’s projecting his own guilt onto the Titans because he blames himself—he was an absolute jerk to that kid, abandoning him in the snow.

Deathstroke, as I see him, is a real guy dropped into a comic book world. He just looks at the Justice League in their silly costumes and finds the whole thing ridiculous. He’s like Deadpool, minus the insanity. He’s not an anti-hero; he’s a villain, a really bad guy. That was the first thing you saw in my first issue—Slade being a complete jerk to his kid. He’s done too much to be walked back.

PC: I also remember the Power Girl (Tanya Spears) dog-killing incident from that run! Fans got very upset about that.

CP: We got so much hate mail! The point of that scene was that Power Girl (Tanya Spears) was trying to save him, but he knew if he allowed her to hang around him, she would start becoming like him. He needed to turn her against him. He was petting the dog, saying, “I’m a bad guy,” and then he snaps the dog’s neck. She’s horrified, she flips out, and goes after him. He says, “That’s much better. Yes. See, villain.”

He’d killed all those people, but he kills one dog, and suddenly I have to fight DC to get the scene published.

PC: You had an interesting use of faith and scripture in Deathstroke #20.

CP: That was my favorite issue of the run. Slade had renounced evil and was trying to put together his own version of the Teen Titans. He tries to recruit Power Girl and uses her Christian faith against her. He quotes scripture about forgiveness, essentially saying, “You have to forgive me because that’s the rule.”

That issue was loaded: the villain was a homosexual born-again Christian, and Slade’s good son, Jericho, tried to kill him to keep their secret affair from his female fiancée. The villain forgives Jericho and quotes scripture, and Jericho breaks down because he can’t accept it. I laid my “minister thing with a trowel” and was shocked DC allowed me to print what was essentially a gospel tract. It just shows that sometimes, stuff gets through and tells a raw, real story.

On Writing, Editing, and Collaboration

PC: You’ve done both editor and full-time writer jobs at Marvel and DC. Which one is harder?

CP: It depends. When I was an editor under Jim Shooter, I had very little autonomy, and there was a lot of pressure to execute his plans.

The stress as a writer depends on your editor. Working with writers like Denny O’Neill or Mark Waid was much easier because they understood story and could actually help put the puzzle together. When I worked with Andy Helfer on Green Lantern, Denny’s idea was to ground it in real science, but Andy’s approach was, “It’s magic. Make a giant boxing glove.” That creative whiplash was tough.

A good relationship is like the one I had with Alex Antone, my Deathstroke editor. It started badly—I wanted off the book—but at some point, we clicked and got along famously. It all depends on whether you’re clicking creatively with the person on the other side of the desk.

PC: You’ve worked with many top artists, like Joe Quesada, Carlo Pagulayan, and Joe Bennett. Is there a different process for each?

CP: Yes, it depends entirely on the artist.

For Ergun Gunduz (Vampirella), it took me a while to adjust to his manga/anime style, but once I got it, I started writing toward his style. I’ll start with detailed scripts, but as I trust the artist, they get simpler. I once just wrote “Gravat: It’s a big monster, make it up,” and he delivered. That’s how much I trust him.

With Joe Quesada (The World to Come), I give him as little as humanly possible because I know he’s going to rewrite me. He is an evil genius mastermind who gives 30 pages of single-spaced, detailed notes on everything from the history of the Vatican to whether a beer cooler lid is up or down. Our collaboration is a true 50/50 partnership, which is why I insisted on his name going first.

Carlo Pagulayan (Superman Lost) is the perfect mix. I trust him implicitly. His storytelling style is so clean and clear that I often don’t even look at the thumbnail layouts. A sequence like a character scaling an ice wall and then running through a jungle to find Clark Kent’s mailbox was so visually clean that it needed little from me.

Sometimes I get ambushed when a script written for one artist’s strengths is given to another, but that is the nature of comics.

PC: Thank you for reading our conversation with Christopher Priest. Be sure to check out The Last Spartan: Red Tape and Black Panther: The World to Come to experience the unique vision of this legendary writer.